Disease characteristics

ETIOLOGY

Equine Infectious Anemia (EIA) is a widespread disease of equidae (horse, donkey, mule, bardot) caused by a member of the Retroviridae family, genus Lentivirus and transmitted mainly from insect vectors, especially forest and horse flies. Its spread is greater during weather conditions favourable to arthropod activity and is more easily detected in regions with humid hot weather: for this reason it is also known as “swamp fever”.

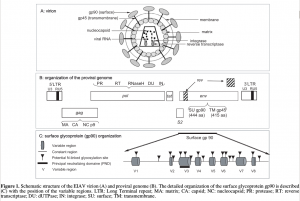

The virus is an RNA virus with a 8.2 kb genome, that replicates in the cells of the white blood line. Specifically, in macrophages, the virus integrates its genome, ensuring the persistence of viral infection over time.

Structure of the virion is displayed in the figure:

(from Leroux C., Cadoré J.L., Montelaro R.C. Equine Infectious Anemia Virus (EIAV): what has HIV’s country cousin got to tell us? Vet Res. 2004 Jul-Aug;35(4):485-512)

TRANSMISSION

In natural conditions, the indirect transmission of the virus is predominantly mediated by vector insects. Haematophagus insects, mainly forest and horse flies, are able to transmit the infection mainly following biting of subjects in the acute phase of the infection and subsequent blood feeding on healthy animals.

Another transmission path of the virus, even more efficient, is the iatrogenic one:the use of contaminated instruments (needles, syringes, and surgical instruments) and transfusions of untested haemoderivative are the most frequent causes. In these cases the infection can also be transmitted from animals with chronic infection, due to the amount of inoculated blood, higher than that of insects.

The passage of infection during pregnancy is less frequent but possible. Contagion is also possible at birth or through secretions and excretions such as colostrum, milk and semen of subjects, especially in the acute phase of infection.

SYMPTOMATOLOGY

The commonness of asymptomatic infections on the one hand, and the absence of specific symptoms and extreme individual variability on the other make the clinical diagnosis quite difficult. The incubation period of the disease may last from 5-7 days to 3 months. Types of circulating viruses and inoculum doses, together with inter-and intraspecific variability, strongly affect the course and evolution of the infection, which can be acute, chronic, inapparent or asymptomatic.

Acute illness manifests itself within 1-4 weeks of infection and can evolve in severe form. The virus actively replicates in the host tissues and can lead to the affected animal in a short time, sometimes even before the appearance of clinical signs; The main symptoms that characterize it are fever and a dramatic reduction in the number of circulating platelets.

Most affected subjects survive. Thus, the infection may evolve to a subacute or chronic form, with recurrent fever-associated cycles associated with depression, weight loss, anemia, and appearance of pointy mucous hemorrhage; Febrile episodes are associated with viral reactivation that can be favored by either stressful events or immunosuppression (eg, corticosteroid administration).

Over time, the frequency and intensity of clinical manifestations diminish, and generally within a year of infection, the immune system of the affected subject is able to keep the infection under control; This phase is characterized by a limited viral replication with no clinical manifestations.

Inapparent carriers of the virus remain infected for the rest of their lives and may be a source of contagion for other target animals; For this reason, although asymptomatic infections are the most frequent, positive animals are subject to restrictive measures to limit spread.

CLINICAL SIGNS:

- fever(>40°C)

- depression

- hemorrhagic petechial

- thrombocytopenia

- anaemia

- oedema

- anorexia

- asthenia

- tachypnea

- sweating

- weight loss

- epistaxis

- jaundice

- irregular heartbeat/weak pulse

- colics

- miscarriage

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS:

- Equine Viral Arteritis

- Babesiosis

- Ehrlichiosis

- Leptospirosis

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS

Given the high frequency of asymptomatic forms and the absence of vaccines, the main diagnostic tool are serological assays as reported by Equine Infectious Aenemia OIE Terrestrial Manual Chapter.

The official test for international trade is Agar Gel Immunodiffusion (AGID) also known as Coggins Test. The negative result indicates that there are no antibodies available at the time of examination while a positive one indicates that the horse is infected and is a carrier of the virus. The method, which has high specificity characteristics, is, however, not sensitive.

The ELISA test, now widely employed in the laboratories, is much more sensitive and offers the advantage of faster execution (few hours than 48/72 hours of AGID). It is used as a screening method and in the case of a positive result it must be checked in AGID in order to exclude possible non-specific reactions.

Immunoblotting is the most sensitive and specific method that can detect the presence of antibodies directed against the three major proteins of the virus (p26, gp45 and gp90)and can address non-conclusive cases when the poor sensitivity of AGID is not able to detect the presence of low-level antibodies.

Foals born from infected mothers, for the presence of antibodies taken with the colostrum, can constitute false positives. To exclude these circumstances, we recommend further tests beyond the sixth month of life.

Alongside traditional serological techniques, molecular methods can be a valid diagnostic aid for the identification of acute infectious (in which the antibody response may not be present) or also, to conduct diagnostic and epidemiological investigations to study the origin of circulating viral strains.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

International Data

National Data

RISK FACTORS

Since there are no specific therapies and vaccines for AIE, prevention is the only means of control the spread of infection. To reduce the presence of the EIA and to limit contagion, it is essential to know the individual health status and the equine population and to ensure the proper management of positive animals and outbreaks. The incomplete implementation of equidae identification still determines the presence in the national territory of subjects with unknown health status that may be a source of contagion for other healthy receptive subjects. The absence of a census of the actual equine population makes the correct definition of the epidemiological framework even more complicated.

As for the management of outbreaks, the frequency of asymptomatic forms makes it difficult for owners to accept AIE diagnosis and isolation of positive heads: this exposes other subjects to possible contagion, considering the type of persistent infection that characterizes the disease. In order to limit the spread of the infection, given the means of transmission, it is also necessary to ensure proper hygienic management in breeding, especially for healthcare practices, and compliance with the expected biosecurity standards.

BIOSECURITY IN EQUINE PREMISES

BIOSECURITY IN EQUINE PREMISES (Italian Version)